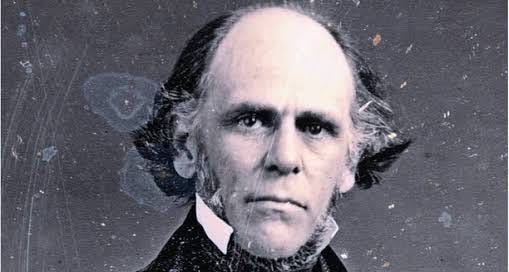

William Henry Brisbane

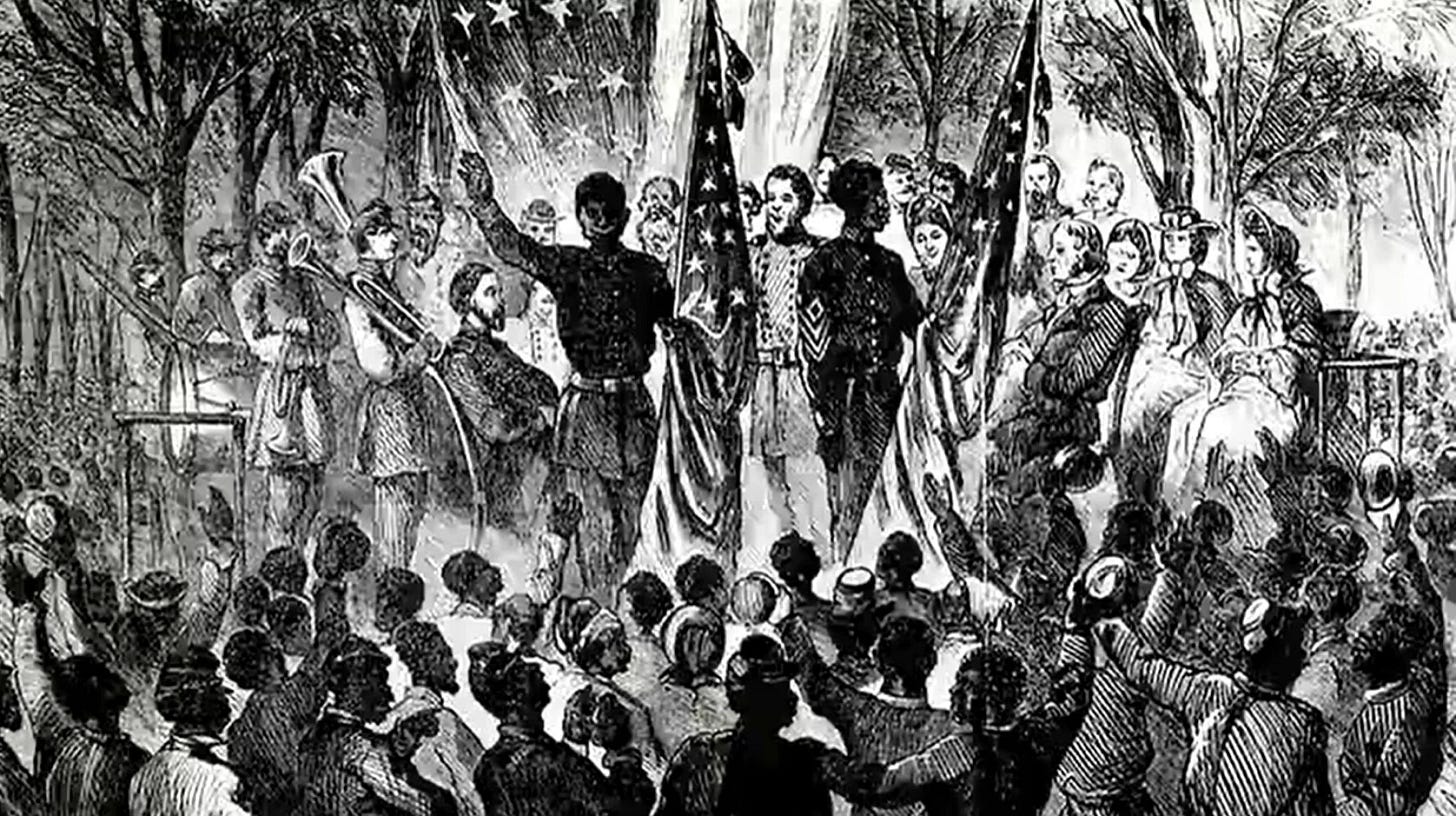

On January 1, 1863, 20 months after the Civil War began, Blacks and Whites gathered in Port Royal, SC, to celebrate an unprecedented moment in American history. Before the war, the residents of Port Royal rarely gathered in mixed crowds. Now, everything was different.

The crowd sang, prayed, and heard the Rev. William Henry Brisbane read President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. As Rev. Brisbane read the document to the crowd, he recognized a Black man in the audience. He was a man Brisbane had once enslaved but now was listening to his former enslaver as a free man.

That man's name is unknown, and we do not know if the two men spoke to each other that day. Still, it marked a poignant moment in Brisbane's remarkable transformation from wealthy enslaver to staunch abolitionist and the Black man's transition from slavery to freedom.

William Henry Brisbane was born in 1806, the son of a wealthy slave-holding father in the Beaufort District of South Carolina. Brisbane's plantation was typical of those in the Low Country in the early 18th century. The soil and climate created excellent conditions for growing cotton. Slavery provided plantation owners the labor needed to produce the crop on a profitable basis. Plantation overseers enforced harsh working conditions on enslaved African Americans. They used whips to punish enslaved people they perceived to be slacking off. The brutal system made South Carolina's low-country planters some of the wealthiest people in Antebellum America.

As a young man, Brisbane saw nothing wrong with the system. He later recalled defending the system with the "zeal and energy of the warmest supporters of the South’s ‘peculiar institution.’" By the time he was twenty-seven years old, he ran the plantation supervising two dozen enslaved field workers and their "drivers."

His wealth gave Brisbane the freedom to pursue his intellectual interests. He became a Baptist minister, accepted a pastoral role in a local church, and began publishing essays defending slavery in the Southern Baptist, a newspaper he founded in 1835. He carefully examined each mention of slave or slavery in the Bible. He claimed that a "man's mind must be awfully perverted by prejudice who does not see …" in the Bible "a sanction for slavery." Brisbane was convinced that God sanctioned slavery.

Brisbane's transition from enslaver to abolitionist began that same year. The American Anti-Slavery Society organized an abolitionist postal campaign they hoped would "sow the good seed of abolition thoroughly over the whole country." They raised $30,000 (over $1 billion today) for the campaign, collected the names of "prominent gentlemen" in the South they hoped to influence, and published pamphlets calling for the immediate end of American slavery. Brisbane was one of several "prominent gentlemen" in South Carolina sent abolitionist literature in the campaign.

On July 29, 1835, men broke into the Charleston, SC Post Office and stole a sack of mail containing much of the literature sent to men in the area. The next night, a mob of over two thousand watched as the men burned the literature. They also burned three abolitionists in effigy. When he heard about the incident, Brisbane deplored the mob violence but defended the destruction of the abolitionist literature. He feared its distribution might lead to a slave insurrection or the destruction of South Carolina's social system.

Some of the literature survived the mob's efforts and reached Brisbane later that year. One pamphlet Brisbane read was an excerpt from a book by Francis Wayland entitled “Personal Liberty.” Reading the material moved Brisbane to reconsider abolition. He concluded, slavery was incompatible with the nation's republican principles. "If freedom was good," he wrote, "then slavery was evil."

Yet Brisbane was not willing to call for immediate emancipation. He feared emancipation might destroy the economy and subject Black people to retaliation by Whites unless there was a plan to "return them to their native land."

Like many in Antebellum America Brisbane assumed that emancipation must be accompanied by the deportation of African Americans to Africa. Most White Americans did not believe that Whites and Blacks could live side by side after emancipation. Therefore, most emancipation called for some method of separating the two races. Expatriation was one of three commonly held assumptions about how best to accomplish emancipation. Most Americans also assumed that emancipation must be gradual and that there must be compensation for the financial impact on the enslaver.

Brisbane made life easier for the people he held in bondage after reading the abolitionist pamphlet. He fired his overseer and banned the whipping of enslaved people. He granted the enslaved the right to farm independently. But he did not call for abolition. He declared he "would rather be called an assassin than an abolitionist."

Yet, his neighbors thought that was precisely what he was becoming. There were warrants issued for his arrest, so Brisbane left the state before he became a victim of "lynch law." In 1838, Brisbane sold his enslaved people to his brother and moved to Ohio with his family.

In Ohio, Brisbane continued to consider slavery in the United States. He read a copy of American Slavery as It Is, a book by Timothy Weld that compiled first-hand accounts of slavery's brutal reality. As he read Weld's book, he shifted from wanting to write a rebuttal to becoming convinced abolitionism was right. Slavery had to go!

In 1840, Brisbane began making amends for his involvement in slavery. He re-purchased the enslaved people he sold to his brother for an above-market price of $10,000 (nearly $360,000 today). Next, he provided each enslaved person with documentation confirming their emancipation and he facilitated relocation for several individuals to Ohio.

Union forces seized control of Port Royal Sound and the Beaufort District in early November 1861. Nearly every White plantation owner abandoned his land during the assault. Most of the enslaved people remained on the land. The situation forced President Lincoln and his cabinet to think about the political reunion of the nation following the war, the rebuilding of the shattered South, and how best to integrate any formerly enslaved people emancipated by the war—a process known as Reconstruction.

Emancipation Day, January 1, 1863, Port Royal, SC

Port Royal became an early experiment in Reconstruction. Missionaries, both men and women, came to South Carolina to educate the freed people. Northern investors and military officers worked to maintain cotton production. They hoped that profits from the sale of cotton would help finance the war. Other abolitionists dreamed of an opportunity to show the nation that free labor was superior to enslaved labor. They believed assisting the enslaved people's transition to freedom was the best way to achieve that goal.

Only one man did not receive from Brisbane the documentation free Blacks needed to prove their freedom following his emancipation of his enslaved people. No one could locate him in 1840. Somehow, he made his way to Port Royal and attended the Emancipation Proclamation celebration on New Year's Day, 1863. He witnessed William Henry Brisbane, his former enslaver and now a committed abolitionist, reading President Lincoln's proclamation. Brisbane recalled making eye contact with his former "property" as he received the news that Emancipation Day had arrived.

Few White enslavers voluntarily freed their slaves. Few were willing to sacrifice their wealth, community status, and family connections. The pressure to conform to the slave system’s demands was enormous. Yet, William Henry Brisbane rebelled, and discovered God did not exist only on paper but in the faces of other human beings.

Further Reading

Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment by Willie Lee Rose

This book was published in 1864. It may be hard to find or expensive if you do find a copy. It is, simply put, one of the finest historical narratives I’ve ever read. Willie Lee Rose was a gifted historian in an era when women historians were rare. Unfortunately, for Rose and us, her life was cut short by a series of strokes.